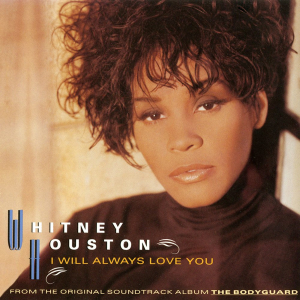

3 December 1992

Thump, and then The Note Heard Round The World. I almost feel stupid trying to consider Whitney Houston’s ‘I Will Always Love You’ as any normal record. Despite the efforts of Celine Dion and Mariah Carey, that teed-up money note by Whitney is the emblematic gesture of the ’90s power diva vocal style. However, there’s a whole three minutes before that climactic event, and another minute after.

The build-up to that moment is much longer than three minutes. I’ve already referred to Mariah Carey’s showboating high note at the end of her 1990 debut ‘Vision Of Love’ as the starting whistle for that ’90s fashion for loud, ostentatious female vocals, coming as a counter-balance to the Milli Vanilli lip-syncing scandal that embarrassed the US record industry the same year. Whitney had some loud ones in her ’80s repertoire, most notably the 1988 Olympic anthem ‘One Moment In Time’, but her own 1990 material, from her album I’m Your Baby Tonight, was mostly R&B-flavoured uptempo pop along with old-school soulful ballads. Still, come the new demand for flashy melisma and power-hosing top notes, Whitney already had all this in her locker.

In fact, the rest of Whitney’s ‘I Will Always Love You’ is just as showy as The Note. After all, it starts with Whitney a cappella for the whole first verse, clearly to establish the requisite awe. Once the music finally comes in for the first chorus, and then through the second verse, she’s restrained. We probably forget that for the second chorus she also hits a demonstrative hard, long note that most singers would consider their show-stopper. But we’re not even halfway through the song; this is just Whitney finding her range. We now get a cheesy, meandering sax break before Whitney comes back with another restrained verse; it’s as plain as day that the track is building to some sort of climax. And then it hits us.

I haven’t mentioned Dolly Parton’s original recording of her own song yet, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, I don’t recall hearing it being played around the time of Whitney’s chart-topping cover version; I’m of the impression that the Dolly-Whitney comparisons come later. Secondly, we can take it as read that any cover version of a Dolly song is a lesser artefact. However, revisiting the original reveals one crucial difference between the two: for the final chorus with that big note, Whitney adds a key change. At the best of times, a melodramatic key change is a rotten device: lazy shorthand for ’emotion’. In Whitney’s ‘I Will Always Love You’, the worst of times, it just copperfastens the impression of a tender ballad being callously power-hosed and sand-blasted to death just to show off the singer’s voice. That final post-climactic minute is a long, tedious portfolio of melisma.

I’m loath to use words like ‘worst’ when I know that there’s a decade of Celine Dion to come. Whitney Houston is a far better singer, and ‘I Will Always Love You’ a much better song, than anything we’ll hear from the Foghorn of Quebec. And yet there’ll always be a uniquely bad taste in the mouth—and a ringing in the ear—from this cheap, calculating piece of record industry tat.